Two blind AT students commute from Aurora to room 217 each morning in pursuit of continuing their education at one of the largest VISION programs in Illinois.

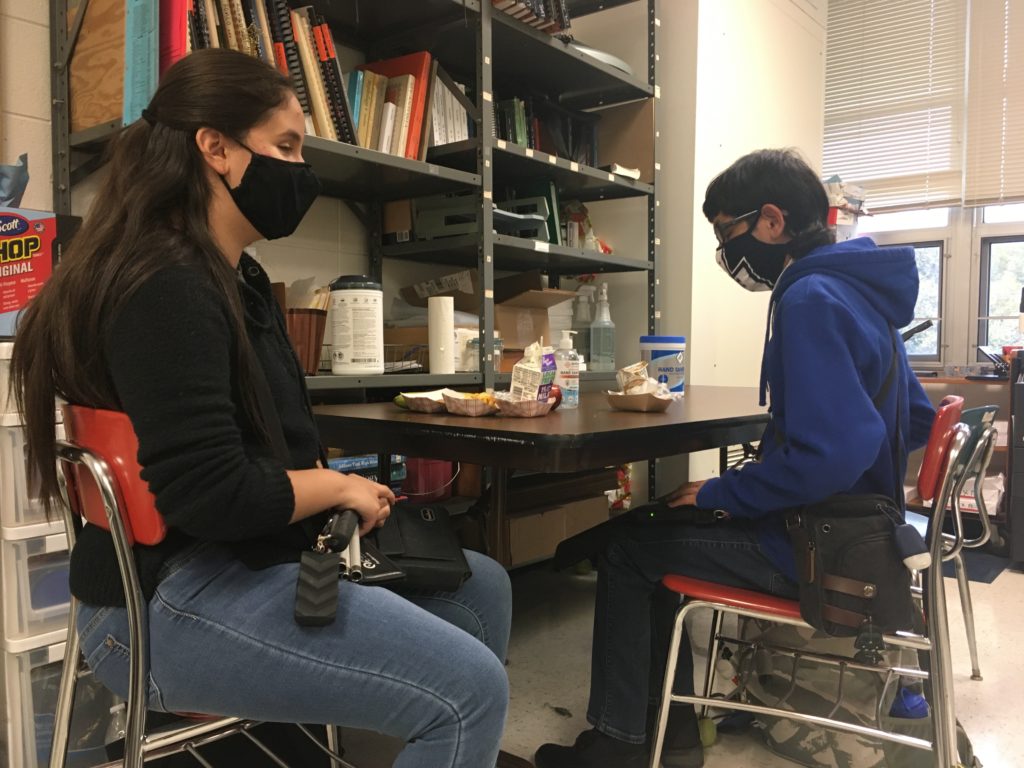

Seniors Karen Gonzalez and Daniel Zuniga have attended school together since kindergarten at Stone Creek Elementary, Albright Middle School, and now, AT. Though their school day schedules follow the same format of a sighted student, their morning starts earlier as they prepare themselves for a daily commute to school that is much longer than what most Blazers endure.

“We both come in from far away. As far as Aurora, actually. We get here a lot earlier than most people, but by the time we arrive, the school is alive,” said Zuniga. “This year, they provided a van for us. They used to take us to North Aurora when we had four people, but now it’s just both of us.”

Gonzalez and Zuniga emphasized that because the longer commutes have always been integrated into their daily lives, the commutes are no strain or a cause of discomfort.

“You get used to it. I try to do my homework,” said Gonzalez.

Their schedules consist of eight full periods, some of these defined as mainstream classes, and others as specialized classes.

Zuniga explained the difference between mainstream and specialized classes. “A lot of the classes we take are referred to as mainstream, basically, like any normal class. So, for example, my first hour would be child development, (which is a mainstream class). The classes we take here (in room 217) are more specific to our needs. Mainstream classes are a larger environment, and everyone has their own opinions. Some of us absolutely love it. Some of us hate it.”

Because of the VISION program’s nature, both Gonzalez and Zuniga have been mainstreamed most of their school careers.

“I’ve been mainstreamed most my life. I want to say middle school through high school years. Most of my classes are with sighted people, except for math. They are different; these [specialized classes] are easier,” said Gonzalez.

Gonzalez takes English 12, Math Resource (ALEKS) , AP Psychology, Activities of Daily Living (ADL), PE, Creative Writing, Lunch, and Study Hall, respectively. ADL teaches basic life skills like folding clothes, cooking, turning on a stove or oven, and laundry.

“They are focusing with me more on the stove and oven because my mom doesn’t really know how to teach me how to,” said Gonzalez.

Zuniga takes Child Development, Math Resource, AP English Literature & Composition, Chamber Orchestra, PE, Creative Writing, Lunch, and Study Hall, respectively.

Outside the classroom, Zuniga is a violinist for the school orchestra, and a member of the Philosophy Club. Gonzalez is interested in Psychology and Philosophy Clubs. Both students are involved with a Paralympics sport called Goalball.

“It’s quite popular in the visually impaired community, actually. It’s very fun, quite intense if the leadership is right,” Zuniga explained.

The game consists of a square court of three members on each team. The teams roll a ball and belt it back and forth until a goal is scored, defined by the ball rolling behind the other team.

“To block it, you literally lay on the ground flat and block it with the entire length of your body,” Zuniga describes. “It can get intense. If anyone thinks we’re fragile, their opinions completely change once you see the sport.”

The team travels to other states housing schools for the visually impaired, like Iowa, Wisconsin, Missouri, and AT hosts some Goalball tournaments. Through visiting schools solely for the visually impaired, Gonzalez and Zuniga have noted key differences between integrative programs versus schools for the visually impaired.

“[These schools] are way older than some of the schools here because the mindset was, if you’re disabled, you have your own school. These schools, ISVI, Lawrence, Jacksonville– they’re in the middle of nowhere,” said Zuniga. “These programs [VISION] offer the technology, tools, and education we need, so that we can, for lack of a better term, survive in this world.”

Gonzalez notes the distinction between students attending the two institutions.

“They’re very sheltered, blind people who went to the specialized school. You can tell [the difference]. And, they’re just surrounded by teachers who know what they’re doing with blind people, so their social skills are sometimes not good, for lack of a better term,” said Gonzalez.

Zuniga agreed, reinforcing that AT’s environment best prepares him for the real world.

“Because you were exposed in mainstream classes, but Karen and I, we have multiple mainstream classes. So, we mixed with everyday society over there,” he said

Most AT classes have provided adequate resources for Zuniga and Gonzalez, but a few have offered close-minded instruction, underestimating the students’ skills, forgetting their physical disability has no effect on their mental capabilities.

“When we took one class, the teacher underestimated us. When someone is, for lack of a better term, ‘disabled,’ everyone underestimates you. We’re not everyone, but the vast majority underestimates us, they think we’re incapable. They think that because we’re missing a sense, we also have some other disabilities,” said Zuniga.

Zuniga and Gonzalez feel that there has been bias in how they are not only treated, but how they are graded.

“We got too many free As for my liking. We asked to turn in an assignment late because we were struggling with finding some information. The next day, before we even turned it in, we were looking at Powerschool, and we had a 10/10 on an assignment we never even turned in,” said Zuniga.

“They pity you because of your blindness. So, if you got something wrong, they would give you an A instead of helping you,” said Gonzalez.

The students know when they are treated unfairly, and Gonzalez is the first to speak up.

“I get that you have to respect teachers and not talk terribly to them, but I have to give sassiness I get,” said Gonzalez.

Zuniga describes Gonzalez’s tenacity. “She has the fire. I don’t. I’ve always admired her for this ability because of the way she has comebacks. It is matter-of-fact, to the point, and hits where it is supposed to hit.”

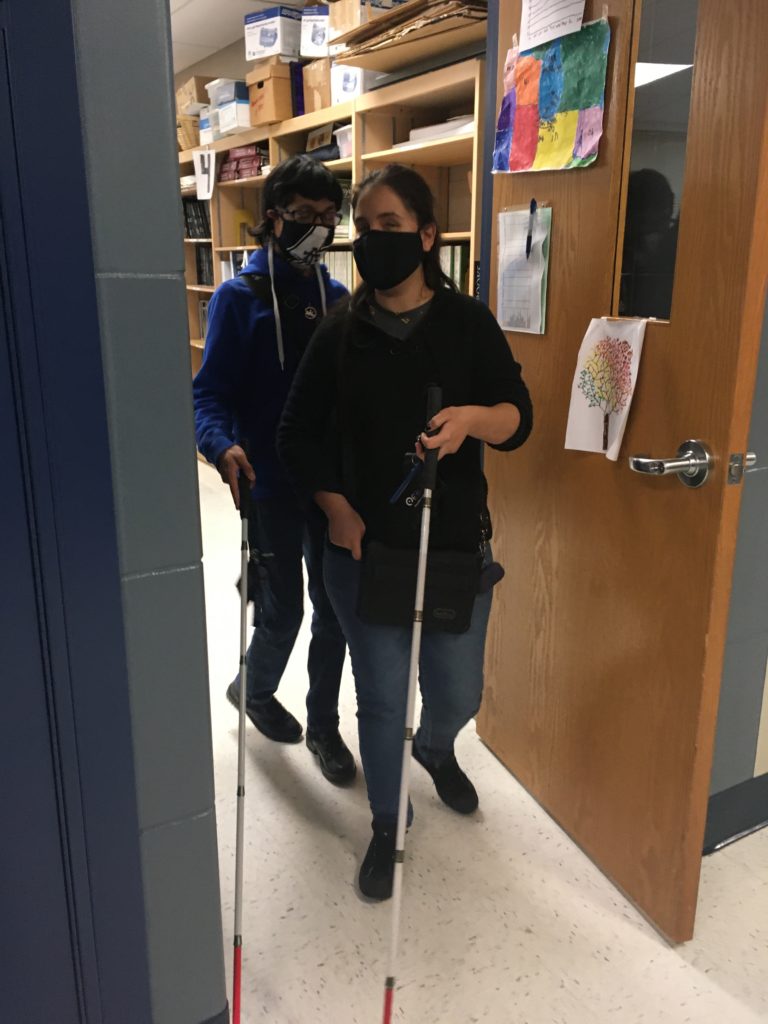

Zuniga and Gonzalez describe the adventure of navigating the hallways between classes.

“It can be scary and adventurous sometimes. A lot of people are like, wow, I don’t know how you can do it. We can do it thanks to technology, our situational awareness,” said Zuniga.

The two have grown accustomed to accidental crashes and extravagant apologies by other students. They assure other students that they are tough enough to withstand the collisions of AT hallways.

“Some people will overreact if they brush a little. We’re fine. We’re not fragile. If anything, maybe we’re slightly stronger sometimes,” said Zuniga.

“The way I would describe it to people who’ve never observed it is like the roads at an intersection when you hear the siren of a police car and ambulance. Everyone starts saying, ‘Where do we go? Where do we go?’ I feel like some people react that way when they see the cane,” said Zuniga.

Zuniga and Gonzalez would like to encourage students and faculty to understand they are no different from sighted people. They take roundabout ways, with some tweaks here and there, but at the end of the day, they work no differently from sighted people.